The outcome of an encounter between the Swedish musician-producer Karl Jonas Winqvist and musicians from the Toubab Dialaw village in Senegal, this collective recording, which evolved through jam sessions and WhatsApp exchanges, represents a strange vessel that traverses the Mediterranean soundscape. Read PAM’s full interview.

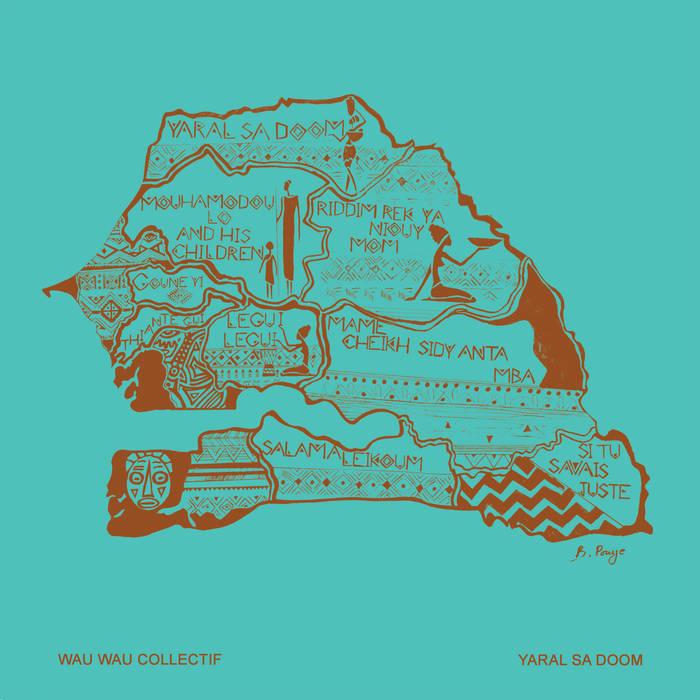

This is one of the more surprising releases of early 2021. Yarel Sa Doom (the title is an homage to Super Diamono de Dakar) is the result of a spontaneous encounter between Senegalese musicians (poets, percussionists, beatmakers…) and the Swedish musician-producer Karl Jonas Winqvist, an artist in residence for three months. A combination of circumstances resulted in the creation in Toubab Dialaw of the Wau Wau collective, which was supplemented thanks to WhatsApp exchanges and additional contributions by Swedish musicians. The result is a futuristic voyage, a strange, captivating and experimental soundtrack. In a refreshing change from typical world music productions, the compositions are either written collectively or shared: by the singer-bassist Aruna Kane, his Senegalese partners and Winquist. This demonstrates the singularity of a project that emphasizes the collective over the individual. Even if this means heading in different directions: a quirky ballad, a unique reggae riddim, a dream-like flute evoking Sufism, sprinkling percussion and delicious beats, echoes of fanfare and wise words addressed to the world, weary pseudo-jazz melodies interpreted by an ageless singer and latin afro-funk grooves in the vein of the classics of the genre… It’s a long list, but what is striking is the natural overlapping between what emerges from music captured in the moment and the discreet additional production work used to enhance it. Hear about the production process from the man behind this singular project.

What was your musical background before this project?

A very eclectic one. I guess it all started 20 years ago when Jenny Wilson and I released our debut album There is Hope with our experimental pop band, First Floor Power. We played a lot in Europe and released some more albums. Fast forward to 2015 when I started to broaden and widen my musical activities. I started to host the 2-hour show ”Kaejdoskop” on Swedish National Radio where we play music from all corners of the world without any commercials. I still host this show now and then. I also started up my own one-man label Sing a Song Fighter. Basically, I did it to turn a dream into reality, to reissue one of my favorite albums: Idrissa Soumaoro & L’eclipse, the first studio recordings with the then-teenage duo Amadou & Mariam, along with their music teacher Idrissa. I’ve been listening to scruffy mp3’s of this rare and elusive album for a long time. Then I started my mission to locate Idrissa, to find a master or an unplayed original album etc. When all this succeeded after some hard work, I contacted my friend Eric who ran the great US label Mississippi Records to see if he wanted to co-release it with me. I really wanted the album to become widely available and needed some experienced collaborators. So, that was the start of my own label. And now I’ve released over 40 albums over the last six years, from Swedish prog music, to African music, solo piano pieces and jazz albums… A mixed bag, just how I like it. I also started my own solo project called Blood Music and started to produce other artists (mainly Swedish artists, but I’ve also had the honor to produce the encounter between Senegalese kora master Lamine Cissokho and Indian steel guitar master Manish Single, as well as the Scottish singer/songwriter James Yorkston and the Congolese Dekula Band to mention just a couple).

How and why did you come to Senegal?

I came to Senegal in 2018. The Swedish Cultural Arts body had this new Musical residency exchange grant to Senegal and since I have been heavily in love with African music and culture for many years I happened to apply for it. I was chosen to go so, I did, on my own without having ever been to Africa, speaking French or their language wolof. So, I arrived there as a child not knowing anything about anything and couldn’t express myself that well or understand much, either. But I was prepared. I wanted the challenge and the experience of being lost and in need of people … The cultural exchange between Sweden and Senegal was based at this great hotel/cultural hub called Sobo Bade in a town called Toubab Dialaw, a few miles from Dakar and there are enough moments and scenes from this 3-months trip to fill a book. I made close friends there. Every night I ended up jamming with the local musicians and I wrote some new music and time just flew. Once I was standing in the small airport in the middle of the night preparingto go home to Sweden I felt sad and, all of a sudden, a voice called out. The Air France pilots went out on strike! All flights were cancelled and I ended up going back to Sobo Bade. It got me an extra week and the musicians there quickly decided that now was the time to do something more than just jamming… We went to the local musician Arouna Kane’s place and he had some studio equipment laying around. We gathered musicians and just started to create music together, staying up all night and really discovering some special together. I had only brought this electric harp (like a small toy instrument) with me, my omnichord and so I created some songs on that which, along with the Senegalese musicians, got this surreal and lovely atmosphere going. We were only five-six people and it was like it was our secret. When I finally left for Sweden I left the recordings in Toubab Dialaw because the band wanted to continue and then send them me. Time went by and I received this and that through WhatsApp. New songs, overdubs … we learned that we wanted to make this music in our own special way, where my vision blended with theirs. So I started to record overdubs in Sweden as well and the project just grew and grew.

What was Arouna Kane’s role?

Arouna was the technician. It was at his place/studio where we started it all up. He was also the bass player and sang on some tracks. If it wasn’t for me and him continuing to send stuff to each other this album would not exist. We knew our chemistry was special!

Did you always want to rework these sessions once back in Sweden?

We did not rework the music. We recorded things and added them to stuff I did in Senegal. In some songs, we added just a tiny little thing, like a keyboard. But in some songs, we added more, like horns. It was such an exciting thing to build things on top of each other’s stuff. But it could also be chaotic – I think I had material for 5 or 6 albums in the end. Still, it was all decided from the beginning, so I had total freedom with the material which was a relief, a clear vision of what I wanted.

Who did you record in Sweden? Did you edit the sessions recorded in Senegal?

Some friends in Sweden helped out by playing flute, saxophone, clarinets and stuff. Annarella Sörlin did some wonderful flute parts and we met for the first time in Senegal, but it was not until back home in Sweden that we recorded together. Lars Fredrik Swahn and Andreas Söderström both helped me mix the album and they added some nice things as well. I even met a Senegalese taxi driver in Stockholm who knew the people of Toubab Dialaw. I invited him and his children to the studio, as referenced by the song “Mouhamodou Lo and His Children.” There were no samples being used except on this one where we used a mellotron. All songs had elements from the first recording sessions in Senegal, and some were left almost entirely untouched.

Have you associated Senegalese musicians who had not recorded together?

Yes, I have and I am still in close contact with them all. We have this dream of taking this on tour. But it will be tough, logistically. Since we recorded so much material, I have already mixed the next album. I hope it will not be too long until that comes out as well. It is just as good. Yet, a little wilder and all over the place.

What do you mean by “wilder and all over the place”? What else can you reveal about the next album?

We recorded so much material and me and Aruna sent overdubs, ideas and new songs to each other up till last week, so the songs on Yaral Sa Doom ended up on that album because they were ready first. But there were just as many other songs waiting and almost finished. Now we basically just need to finish the album artwork and then the second album is ready. I want the young Senegalese painter/artist Babacar Pouye to produce the artwork for this album, too. We’ve never met in real life – he lives in Thies – but we send a lot of ideas and messages to each other. The next album will be just as good as Yaral Sa Doom and I guess I shouldn’t say much more than that right now!

One of the successes of the album is that you manage to bring together different musicians and aesthetics, from the most mystical to the most profane. How can we qualify the result? A trip between Senegal and Sweden? A post-analog reverie?

Yes, a trip between Senegal and Sweden. But also a musical trip where things are mixed together into a new and beautiful form.

How would you define your role: arranger? Sound magician? Vibrations catalyst ?

Not sure. I dreamt up how this album would take its shape. And I made all the mixing decisions. All your three suggestions are good, but I’m also just one of many in the Wau Wau Collectif.

Why did you choose Yaral Sa Doom as the title ?

This was decided from the very first night when we started to record. It was one of the reasons why I longed to go to Senegal in the first place. I have been a long-time admirer of the great music from Super Diamono de Dakar. On their greatest album, Ndaxami, there is this fantastic track called “Yaral Sa Doom.” I kept asking people about that band and song when I was there. I guess I was a little obsessed by it and hoped I would find someone who could help me in reissuing it. Then the night before we started to record, I heard the track on a mobile phone somewhere in the dark night. The musicians told me that the lyrics to that song are important and that the title meant “educate the young” … It all made sense. We were surrounded by kids all the time, and I had just recorded a session with a small school class – that track is featured on the next album. So, I just knew that we needed to have Yaral Sa Doom as the title.

Do you believe education remains one of the major challenges in opening up to others?

I believe so, yes. But mostly I just think that education should be offered to all young children in an equal way. It shouldn’t just be young kids learning from old people. It can work the other way around, also. It is magical and important to have connections between a 7 year old kid and a 97 year old person. It’s important for the Wau Wau collectif that we all learn from each other, therefore it is of importance for us to have both young, not so young and old people in the collectif.

Yaral Sa dom, via Sahel Sounds/Sing A Song Fighter available on bandcamp.